August 28, 1776- September 12, 1776,Escape form Long Island, & the effort to hold New York. August 28,29 1776: “The morning of the twenty-eighth [August, 1776.] dawned drearily. Heavy masses of vapor rolled up from the sea, and at ten o’clock, when the British cannonade commenced, a fine mist was falling. Although half dead with fatigue, the Americans had slumbered little, for it was a night of fearful anxiety to them. At five in the morning, General Mifflin, who had come down from King’s Bridge and Fort Washington with the regiments of Shee, Magaw, and Glover, a thousand strong, in obedience to an order sent the day before, crossed the East River, and took post at the Wallabout. The outposts of the patriots were immediately strengthened, and during the rainy day which succeeded there were frequent skirmishes. Rain fell copiously during the afternoon, and that night the Americans, possessing neither tents nor barracks, suffered dreadfully. A heavy fog fell upon the hostile camps at midnight, and all the next day [Aug. 29.] it hung like a funeral pall over that sanguinary battle-field. Toward evening, while Adjutant-general Reed, accompanied by Mifflin and Colonel Grayson, were reconnoitering near Red Hook, a light breeze arose and gently lifted the fog from Staten Island. There they beheld the British fleet lying within the Narrows, and boats passing rapidly from ship to ship, in evident preparation for a movement toward the city. Reed hastened to the camp with the information, and at five o’clock that evening the commander-in-chief held a council of war. 22 PICTORIAL FIELD BOOK OF THE REVOLUTION.VOLUME II. BY BENSON J. LOSSING 1850.

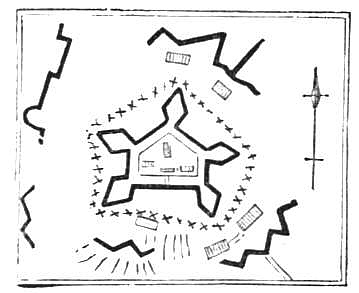

Fort Washington

Source: http://freepages.history.rootsweb.com/~wcarr1/Lossing1/Chap55.html#e035z

http://freepages.history.rootsweb.com/~wcarr1/Lossing1/00-002.gif

|

[22: The council was held in the stone Dutch church (20), which stood near the junction of the present Fulton and Flatbush Avenues. This church was designated in the order for the evening as an alarm post during the night, where they might rendezvous, in the event of the movement being discovered by the British. The officers present at the council were Washington, Putnam, Spencer, Mifflin, M‘Dougal, Parsons, John Morin Scott, Wadsworth, and Fellows. – See Life, &c., of President Reed, i., 417.] An evacuation of Long Island, and a retreat to New York, was the unanimous resolve of the council. Colonel Glover, whose regiment was composed chiefly of sailors and fishermen from Marblehead and vicinity, 23 was ordered to collect and man boats for the purpose, and General M‘Dougal was directed to superintend the embarkation. [23 The uniform of these men, until they were attached to the Continental line, consisted of blue round jackets and trowsers, trimmed with leather buttons. They were about five hundred in number.]

The fog still rested heavily upon the island, the harbor, and the adjacent city, like a shield of the Almighty to cover the patriots from the peril of discovery. Although lying within a few hundred yards of the American lines, the enemy had no suspicion of the movement.(24) [(24) see Pict. Hist. of the Reign of George the Third, i., 273.” Notwithstanding his want of energy on this occasion, General Howe received the honors of knighthood from his king for this victory. The ceremony was performed by Knyphausen. Clinton, and Robertson, in November, 1776”.]

At eight o’clock in the evening the patriot regiments were silently paraded, the soldiers ignorant of the intent; but, owing to delay on account of unfavorable wind, and some confusion in orders, it was near midnight when the embarkation commenced at the Ferry Stairs, foot of Fulton Street, Brooklyn. For six hours those fishermen-soldiers plied their muffled oars; and boat after boat, filled with the champions of freedom, touched at the various wharves from Fulton Ferry to Whitehall, and left their precious burdens. At six in the morning, nine thousand men, with their baggage and munitions, except heavy artillery, had crossed. Mifflin, with his Pennsylvania battalions and the remains of the regiments of Smallwood and Haslet, formed the covering party, and Washington and his staff, who had been in the saddle all night, remained until the last company had embarked. (25) [(25) In his dispatches to the president of Congress, Washington said that he had scarcely been out of the lines from the twenty-seventh till the morning of the evacuation, and forty-eight hours preceding that had hardly been off his horse and never closed his eyes. Yet a popular English author of our day (see Pict. Hist. of the Reign of George the Third, i., 273) mendaciously says, "Washington kept his person safe in New York."]

At dawn the fog lifted from the city, but remained dark and dreary upon the deserted camp and the serried ranks of the foe, until the last boat left the Long Island shore. Surely, if "the stars in their courses fought against Sisera," in the time of Deborah, the wings of the Cherubim of Mercy and Hope were over the Americans on this occasion.

Intelligence of this movement reached the British commander-in-chief at half past four in the morning. Cautiously Captain Montressor and a small party climbed the embankments of Fort Putnam and were certified of the fact. (26) [26 Onderdonk (ii., 131) says that a Mrs. Rapelye, living near the ferry, sent her servant to inform the British of the retreat. The negro was arrested by a Hessian guard, who could not understand a word that he uttered. He was detained until morning, when he was taken to head-quarters, and revealed the secret, but too late.]

It was too late for successful pursuit, for when battalion after battalion was called to arms, and a troop of horsemen sped toward the East River, the last boat was beyond pistol shot; and as the fog rolled away and the sunlight burst upon the scene, the Union flag was waving over the motley host of Continentals and militia marching toward the hills of Rutgers’ farm, beyond the present Catharine Street.(27) [(27) A cannonade was opened upon the pursuers from Waterbery’s battery, where Catharine Market now stands.]

Although the American army was safe in New York, yet sectional feelings, want of discipline, general insubordination of inferior officers and men, and prevailing immorality, appeared ominous of great evils. Never was the hopeful mind of Washington more clouded with doubts than when he wrote his dispatches to the president of Congress, in the month of September [1776.]. Those dispatches and the known perils which menaced the effort for independence led to the establishment of a permanent army. (28) [28 {See page 18.} In his letter of the second of September, Washington evidently foresaw his inability to retain his position in the city of New York. He asked the question, "If we should be obliged to abandon the town, ought it to stand as winter quarters for the enemy?" and added, "If Congress, therefore, should resolve upon the destruction of it, the resolution should be a profound secret, as a knowledge of it will make a capital change in their plans." General Greene and other military men, and John Jay and several leading civilians, were in favor of destroying New York. But Congress, by resolution of the third of September, ordered otherwise, because they hoped to regain it if it should be lost. – See Journal, ii., 321.]

August 30, 1776:

On the evacuation of Long Island, the British took possession of the American works, and, leaving some English and Hessian troops to garrison them, Howe posted the remainder of his army at Bushwick, Newtown, Hell Gate, and Flushing. Howe made his head-quarters at a house in Newtown (yet standing), now the property of Augustus Bretonnier, and there, on the third of September, he wrote his dispatch, concerning the battle, to the British ministry. On the thirtieth [August, 1776.], Admiral Howe sailed up the bay with his fleet and anchored near Governor’s Island, within cannon-shot of the city. During the night after the battle, a forty-gun ship had passed the batteries and anchored in Turtle Bay, somewhat damaged by round shot from Burnt Mill or Stuyvesant’s Point, the site of the Novelty Iron-works. (29) [(29)Washington sent Major Crane of the artillery to annoy her. With two guns, upon the high bank at Forty-sixth Street, he cannonaded her until she was obliged to take shelter in the channel east of Blackwell’s Island.]

Other vessels went around Long Island, and passed into the East River from the Sound, and on the third of September the whole British land force was upon Long Island, except four thousand men left upon Staten Island to awe the patriots of New Jersey. A blow was evidently in preparation for the republican army in the city. Perceiving it, Washington made arrangements for evacuating New York, if necessary. 30

September 7-12:

Lord Howe now offered the olive-branch as a commissioner to treat for peace, not doubting the result of the late battle to be favorable to success. General Sullivan and Lord Stirling were both prisoners on board his flag-ship, the Eagle. The former was paroled(31) and sent with a verbal message from Howe to the Continental Congress, proposing an informal conference with persons whom that body might appoint. Impressed with the belief that Lord Howe possessed more ample powers than Parliament expressed in his appointment, Congress consented to a conference, after debating the subject four days. A committee, composed of three members of that body, was appointed, and the conference was held [Sept. 11, 1776.] at the house of Captain Billop, formerly of the British navy, situated upon the high shore of Staten Island, opposite Perth Amboy. 32 The event was barren of expected fruit, yet it convinced the Americans that Britain had determined upon the absolute submission of the colonies. This conviction increased the zeal of the patriots, and planted the standard of resistance firmer than before. [31. Both officers were exchanged soon afterward, Sullivan for General Prescott, captured nine months before (see vol. i., page 645), and Lord Stirling for Governor Brown, of Providence Island, who had been captured by Commodore Hopkins. Lord Stirling was exchanged within a month after he was made prisoner.

At a council of warheld on the seventh [Sept., 1776.], a majority of officers were in favor of retaining the city; but on the twelfth, another council, with only three dissenting voices (Heath, Spencer, and Clinton), resolved on an evacuation. The movement was immediately commenced, under the general superintendence of Colonel Glover.

---------------------Notes------------------------------------------------------------

<30. On the approach of the fleet, the little garrison on Governor’s Island and at Red Hook withdrew to New York. One man at Governor’s Island lost an arm by a ball from a British ship, just as he was embarking. *

* It was while the Eagle lay near Governor’s Island that an attempt was made to destroy her by an "infernal machine," called a "Marine Turtle," invented by a mechanic of Saybrook, Connecticut, named Bushnell. Washington approved of the machine, on examination, and desired General Parsons to select a competent man to attempt the hazardous enterprise. The machine was constructed so as to contain a living man, and to be navigated at will under water. A small magazine of gunpowder, so arranged as to be secured to a ship’s bottom, could be carried with it. This magazine was furnished with clockwork, constructed so as to operate a spring and communicate a blow to detonating powder, and ignite the gunpowder of the magazine. The motion of this clock-work was sufficiently slow to allow the submarine operator to escape to a safe distance, after securing the magazine to a ship’s bottom. General Parsons selected a daring young man, named Ezra Lee. He entered the water at Whitehall, at midnight on the sixth of September. Washington and a few officers watched anxiously until dawn for a result, but the calm waters of the bay were unruffled, and it was believed that the young man had perished. Just at dawn some barges were seen putting off from Governor’s Island toward an object near the Eagle, and suddenly to turn and pull for shore. In a few moments a column of water ascended a few yards from the Eagle, the cables of the British ships were instantly cut, and they went down the Bay with the ebbing tide, in great confusion. Lee had been under the Eagle two hours, trying in vain to penetrate the thick copper on her bottom. He could hear the sentinels above, and when they felt the shock of his "Turtle" striking against the bottom, they expressed a belief that a floating log had passed by. He visited other ships, but their sheathing was too thick to give him success. He came to the surface at dawn, but, attracting the attention of the bargemen at Governor’s Island, he descended, and made for Whitehall against a strong current. He came up out of reach of musket shot, was safely landed, and received the congratulations of the commander-in-chief and his officers. Young Lee was afterward employed by Washington in secret service, and was in the battles at Trenton, Brandywine, and Monmouth. He died at Lyme, Connecticut, on the twenty-ninth of October, 1821, aged seventy-two years.

32.The committee consisted of Benjamin Franklin, John Adams, and Edward Rutledge. When they reached Perth Amboy, they found the barge of Lord Howe in waiting for them, with a British officer who was left as a hostage. The meeting was friendly, and Lord Howe, who was personally acquainted with Franklin, freely expressed to that statesman his abhorrence of the war, and his sincere personal desire for peace. * The whole interview was distinguished by courtesy and good feeling. Howe informed the committee that he would not recognize them as members of Congress, but as private gentlemen, and that the independence of the colonies could not be considered for a moment. They told him he might call them what he pleased, they were nevertheless representatives of a free and independent people, and would entertain no proposition which did not recognize the independence of the colonies. The gulf between them was evidently impassable, and the conference was soon terminated, for Howe had nothing acceptable to offer. He expressed his regret because of his obligation now to prosecute the war. Franklin assured him that the Americans would endeavor to lessen the pain he might feel on their account by taking good care of themselves. Thus ended the conference. † In the third volume of the collected Writings of John Adams may be found an interesting sketch from the pen of that patriot, describing the events of a night passed in bed with Dr. Franklin at New Brunswick, on the night preceding this conference.

* RICHARD, Earl Howe, was born in 1725, and was next in age to his brother, the young Lord Howe, who fell at Ticonderoga in 1758 (see vol. 1., page 118). He sailed with Lord Anson to the Pacific as midshipman at the age of fourteen years, and had risen to the rank of lieutenant at twenty. He was appointed rear-admiral in 1770, and, before coming to America, he was promoted to Vice-admiral of the Blue. After the American war, he was made first Lord of the Admiralty. He commanded the English fleet successfully against the French in 1794. His death occurred in 1799, at the age of seventy-four years. In 1774, Lord Howe and his sister endeavored to draw from Franklin the real intentions of the Americans. The philosopher was invited to spend Christmas at the house of the lady, and it was supposed that in the course of indulgence in wine, chess, and other socialities, he would drop the reserve of the statesman and be incautiously communicative. The arts of the lady were unavailing, and they were no wiser on the question when Franklin left than when he came.

WILLIAM HOWE, brother of the earl, succeeded General Gage in the chief command of the British forces in America, and assumed his duties at Boston in 1775. He commanded at the attack on Breed’s Hill, and from that time until the spring of 1778, he mismanaged military affairs in America. He was then succeeded in command by Sir Henry Clinton, and soon afterward returned to England. He is represented as a good-natured, indolent man – "the most indolent of mortals," said General Lee, "and never took pains to examine the merits or demerits of the cause in which he was engaged."

† The commissioners immediately afterward issued a proclamation similar in character to the one sent out in July. This proclamation, following the disasters upon Long Island, had great effect, and many timid Americans availed themselves of the supposed advantages of compliance. In the city of New York more than nine hundred persons, by petition to the commissioners, dated sixteenth of October, declared their allegiance to the British government. To counteract this, in a degree, Congress, on the twenty-first, provided an oath of allegiance to the American government.

|